Our loss not theirs

The unhappy endings of two client/agency relationships.

Mistaking relief for redemption (circa 1990)

It looks good on my CV that I worked on the Cadbury account at BBH. Truth is the ads weren’t that great and the client wasn’t that happy.

Unwavering creative surety comes across as an unattractive listening impediment.

BBH had no coping mechanism when its creative vision was out of sync with the client’s, and there wasn’t much that a lowly account director could do about it. Blamed by the agency for not selling the work. Blamed by the client for not effectively representing their concerns to the agency. Caught in the crossfire.

Back then, BBH went out of its way to cultivate an aura of creative infallibility. It was great when it worked for you. You presented work that had the weight of the agency’s reputation behind it. And that meant something. But that same weight could drag you down when things went wrong. Unwavering creative surety comes across as an unattractive listening impediment.

I’d been working on the Dairy Milk brand, which was fine. The earth hadn’t moved creatively but both sides of the relationship were content with their lot.

It was common knowledge that things weren’t going so well with the assortments client - specifically with Cadbury’s Roses. The agency’s first ad for the brand had ticked all the boxes, including creative quality. Now the agency was making very hard work of solving a difficult second album problem. Things had got frosty and fractious. There was a reshuffle in an attempt to loosen things up, and I was brought onto the account.

Roses is a deceptively tough brand to work on: lots of positioning subtleties to navigate. So there were lots of literal boxes, all of which literally had to be ticked for a script to get made. The client had rejected some very good ideas that ticked most of the boxes but not all of them. There was understandable frustration on both sides. But the agency had committed the cardinal sin of letting it show. This gave the client cause to doubt whether we got the positioning, and to wonder whether we we cared to do so. Which was fair enough as I quickly found out.

Inside the agency, the account felt like a broken toy on Boxing Day. Its ideas rejected, the creative department gave up on Roses as an opportunity to do showcase work. As the account director, you’re the avatar for the client in the agency, so it feels like they’ve given up on you too. It was a miserable situation that could do serious damage to an account director’s career.

We tried. The account team did its best to resuscitate the relationship. Morag, the media planner, made it much harder for them to fire us. She added tons of value beyond her bread-and-butter media planning; really solid insight and commercial advice that was easy to action. She was savvy, sparky, and fun. The clients hung on her every word. It was no surprise when she became MD of a leading London media agency.

But it wasn’t enough. An ad agency has to deliver ads. We hadn’t, so Cadbury reluctantly gave up on us. I think they felt sorry for the people on the account team. Knowing that we were listening just made it more frustrating that the agency apparently wasn’t. They decided that BBH wasn’t going to understand the brand, perhaps wilfully so. In their eyes we were trying to make Roses something it wasn’t and didn’t want to be. That doesn’t work in life and it sure doesn’t work in advertising.

Don’t kid yourself if a cold relationship suddenly warms up for no good reason.

So how did it come as a surprise when they fired us? You’d think we’d have seen it coming. In fact we thought we’d turned a corner. The relationship got warmer. Meetings got easier. It felt like we were clicking at last. We started to feel welcome in Bournville.

We thought we were coming out of the woods. In reality we were in the eye of the storm. Things had settled down because the client had decided to fire us. With the decision made, the stakes weren’t high any more. The tension was gone. They relaxed. So there was a period of calm and cordiality while they set things in motion to find a new agency. Then they told us.

We’d naively mistaken their relief for our redemption.

Don’t kid yourself if a cold relationship suddenly warms up for no good reason. You think things have got better. It’s more likely they no longer matter.

When a client buys professional services, subject-matter expertise is a given. The harder and more important thing is that their advisers get them and act accordingly. If you don’t get that, get used to losing your clients.

In case any alumni read this, I’ve just described my only really bad experience at BBH. I had a ball and learned from the best. It was the best agency in town because of its creative standards, but it didn’t always get it right. Who does? It just wasn’t great at handling rejection.

Forgetting ourselves (circa 2000)

The Leith Agency’s logo should have been a skull and crossbones. We were only happy when we were swashbuckling, when we were looting London agencies for accounts and awards that had no business going to Scotland.

He turned the room from po-faced to playful in an instant.

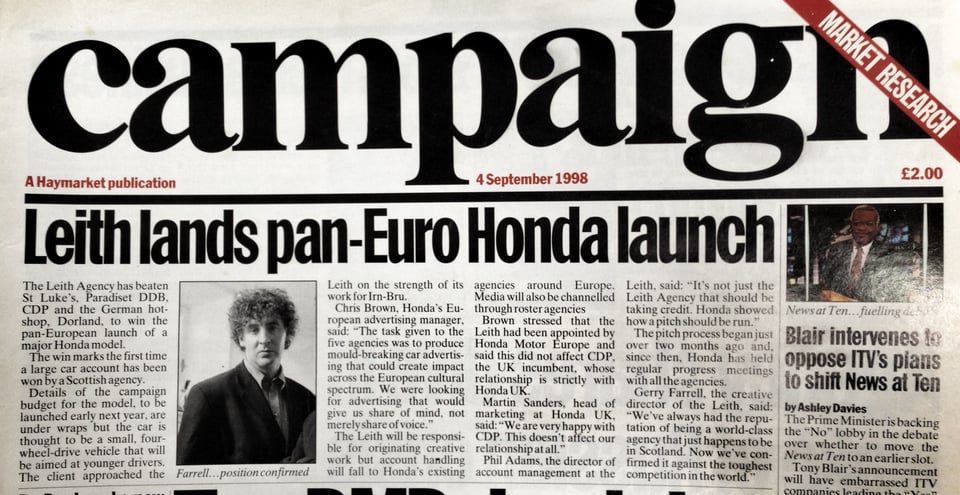

In a moment of peak piracy we won a pitch for the European launch of a quirky new car from Honda, called the HR-V. I can say without hubris that we won it by a mile. The client told us so.

We won partly because we were nimble and made the format suit our style. The presentations were strictly limited to fifteen minutes, maybe twenty. We made sure there were short, straight lines between insight, strategy, and idea. We edited and rehearsed so that we could present slowly and finish early.

We won partly because we were understood. The audience was a mix of continentals and Japanese for whom English was their second language at best. Our pitch was visual, theatrical, and monosyllabic. Punchy AF. I presented the strategy in five minutes using a single three-circle Venn diagram. Gerry, our creative director, had the audience popping bubblewrap. He turned the room from po-faced to playful in an instant.

Our presentation was a professional job.

But the main reason we won was that we presented much more than a car campaign. Honda is a deeply, sincerely philosophical company. The beliefs of its founder, Soichiro Honda, are living ideas that guide the culture to this day. Our idea was based on Honda’s core values (The Three Joys), which were epitomised by this cuddly, charismatic car that we christened “Joy Machine”. In one of our ads the Joy Machine drove over giant bubblewrap in a bubbledome. Joy became an advertising cliché in the decades that followed but it was fresh and interesting (AF) back then.

From there we went on a bit of a run with Honda. However, in hindsight, by running after the money we were running away from ourselves.

Next we won the pitch to launch the new Honda Civic across Europe. The stakes were much higher for this one. The Civic is a make-or-break model for Honda. And the pitch was gruelling: all politics and attrition. This time you could feel the influence of the dealers, who wanted identikit ads with the car looking sexy on wet roads in the golden hour, just like everyone else’s. The pitch went to extra time then penalties. The ads were bland and forgettable. The win felt hollow in spite of its commercial significance to Honda and us.

The HMES account gave me the perverse reassurance that the worst meeting of my career is almost certainly behind me.

After that things went from arduous to absurd. We were appointed as lead agency for Honda Motor Europe South (HMES), whose territory was France, Spain, and Italy. We cobbled together a collective of independent agencies in Paris, Milan, and Barcelona, and did our best to run the account from Edinburgh.

HMES wanted the efficiency of running the same creative work in every country. Whereas each country was determined to do its own thing. As lead agency, we were stuck in the middle. If only I had £50 for every time someone told me that, “What you have to understand, Phil, is that in France/Spain/Italy things are just a little bit different.” Yeah, right. Not when it comes to buying cars.

The HMES account gave me some fun times in Paris, some international advertising lessons learned the hard way, and the perverse reassurance that the worst meeting of my career is almost certainly behind me. It gave none of us any real satisfaction. It’s hard work trying to be something you’re not. Our buccaneering instincts made us ill-qualified for diplomacy, bureaucracy, and lack of adventure.

From the outside it looked like we were doing well with Honda. However, in the time between the HR-V and HMES, there was an insidious change in our relationship with them. We’d gone from pirates to incumbents. We weren’t quite ourselves anymore. We’d lost our edge, with this client at least.

Then came the pitch for Honda UK.

We had our arses handed to us by Wieden + Kennedy.

Everything had led to this, the big one. The UK was the most important market in Europe for Honda. Honda UK therefore had the largest advertising budget and the most influential marketing department in Europe.

The pitch brief was dead clear and apparently simple. Honda wanted to be a cool brand (their words.) And they asked the pitching agencies to show how they’d make that happen by creating campaigns for two cars: the CR-V and the Jazz.

We did as asked. We developed two excellent car campaigns. Gavin MacDonald’s strategy for the CR-V was one of the best pieces of advertising planning I’ve ever seen. And the strapline for the Jazz was, “One proud owner.” The idea was almost identical to the fêted Saatchi campaign for the Toyota Corolla - “A car to be proud of” - that won lots of awards several years later. I think we’d have won this pitch nine times out of ten.

Nonetheless we had our arses handed to us by Wieden + Kennedy.

They were the pirates this time. They ignored the cars and focused on the desired outcome of making the brand cool. Like we’d done for the HR-V, they tapped into Honda philosophy to create the famous Power of Dreams campaign. Many of their ads featured no car at all.

We peaked early with Honda. We went from winning by a mile to losing by a mile. And it turned out to be winner take all. Wiedens didn’t just win the UK account, they ended up with the whole Honda shebang.

We wouldn’t have won this pitch even if we had challenged the brief. What irks me to this day is that it didn’t occur to us to do so. It was incumbent behaviour. It was a brutal lesson. Remember not to forget yourself.

The (unhappy) End.

-

What a great article, Phil. In the late 80s, I was an account handler at BBH's biggest rival, GGT, working under the brilliant but bonkers Dave Trott. When I moved from Leo Burnett, I chose GGT over BBH. However, it sounds like things wouldn't have been very different. I relate so much to what you write here. Being the poor bastard who got shot by both sides, client and agency, was one of the things that drove me out of account management. That said, I do think of GGT as the place where I learnt pretty much everything I know about what makes good advertising. I suspect you may feel the same about BBH.

Thanks Graham. Our experiences do sound similar. Being shot by both sides (not often I hasten to add) was the price I paid for the best advertising education imaginable. It's entirely right that creative businesses should be led (not managed but led) by creative people. However, I found to my joy at the Leith Agency that quality control could be balanced between creative, planning, and account management and still be ruthless. You could accept that a client was right and you were wrong, and collectively bounce back to give them something even better.

-

Wonderfully, incisively written, Phil. What storyteller.

Thanks Jim. Praise indeed!

Add a comment: